VMU Lecturers on the Events of January 13th: There Wasn’t Even a Thought of Not Going If One Could

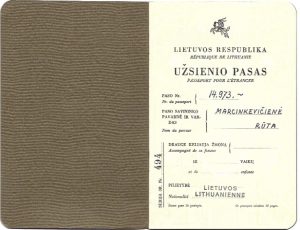

Rūta Petrauskaitė at a rally in Stockholm in 1991 (photo from personal archive)

During the events of January 1991, many felt a duty to be in Vilnius at the Seimas or the Television Tower, while those in Kaunas went to Sitkūnai and Juragiai to stand guard. Vytautas Magnus University (VMU) lecturers and students also gathered at the university’s central building on S. Daukanto Street, hoping to protect not only VMU but also the television station of the Kaunas branch of Lithuanian Radio and Television, which began broadcasting on the night of 13 January, after Soviet paratroopers seized the Vilnius Television Tower.

Enormous tension – hair turned grey overnight

“Everything happened very spontaneously. The example set by those in Vilnius inspired us and showed us that we simply needed to be there, and whatever happens, happens. Of course, there couldn’t be any bonfires, but it still felt very good to be together. Staying at home would have made it seem much more terrifying – the dreadful uncertainty would have been oppressive,” recounted Professor Rūta Petrauskaitė, who started working as a lecturer in the Department of Lithuanian Studies at the re-established VMU.

“On the one hand, these events caught us off guard very unexpectedly, but on the other, it was foreseeable that independence would not come easily,” the professor said, noting that the first day in Vilnius deeply affected all Kaunas residents. Living in Vilijampolė with her family at the time, she remembers how people drove through the streets, calling out through loudspeakers to join and help defend Sitkūnai, where her husband had also gone to stand guard.

“We had a radio and TV, and the repeated calls for people to go, to be present and to contribute really moved people. My son was still little, so I couldn’t leave the first night, but the next night, after leaving my son with my mother, I made my way to the university. There wasn’t even a thought of not going if one could. It was a very unifying, strong moment. The first night, of course, was sleepless, very restless, very difficult; we waited and listened to the news. Our family’s anxiety was not unfounded, as one of our family friends, Antanas Ramoškis, was listed among the injured. I remember that feeling when I approached the mirror in the morning and saw that my temples were grey – my hair had turned grey that night,” Rūta Petrauskaitė recalled.

Observed the Funeral of Titas Masiulis from the Roof

The professor recounted that, contrary to the dramatic events in Vilnius, the atmosphere at the university was quite different: “We hardly knew what we were supposed to be protecting from what because it was so quiet around us.” Students and lecturers settled into small groups in various lecture halls, chatting away, some playing panflutes, others fifes.

“There was such a lyrical atmosphere. The outside doors were, of course, locked, but as I wandered through the building, I found an open exit to the roof. I climbed up on the roof and thought that it would have been very easy to reach the Television building, as there were interconnected roofs. In other words, we weren’t that heroic; we hardly would have stopped armed saboteurs. But that night really brought together the people who were there,” the professor recalled, adding that the next day, from the same roof, she observed the funeral procession of Titas Masiulis, who had died in Vilnius, as his coffin was being transported along K. Donelaitis Street, which was flooded with people.

“On the one hand, the events of January 13th left us with tragic memories, but what happened at the university, our unity, contributed greatly to the spirit of the university, which was still very strong at that time, and to the community itself, which was quite small. These were the early years of the re-established university’s existence. We all knew each other; there were just a couple of buildings and a handful of employees performing various functions,” Prof. Petrauskaitė shared.

Unseen Western World and Lithuanian rallies in Stockholm

The VMU researcher, who experienced the January events in Kaunas, welcomed the coming period of change not in Lithuania, but in Sweden. The young lecturer was invited to teach the Lithuanian language at Stockholm University for six months. There, she joined the Thursday rallies in Norrmalmstorg Square, lined with the flags of Lithuania and other Baltic countries. The rallies were attended by long-standing residents and newcomers, mostly researchers and trainees.

“This was the continuation of January 13th in Stockholm. We would meet, get to know each other, and talk; we had a lot in common, although we were all very different. It’s a pity that I couldn’t see what was going on in Lithuania at the time,” Rūta Petrauskaitė recounted.

During this time, Lithuania, undergoing a social shift and transition to capitalism, was far from resembling the modern capital of Sweden. “The contrast when you leave the still grey, Soviet-style gloomy Lithuania, and within 45 minutes you arrive in Stockholm – you step off the plane, and it’s a completely different life there. Even the airport itself is astonishing: the lights, music, and spaces. I remember that, out of confusion, I followed the pilot of the plane and ended up in a staff-only area,” the researcher smiled. “There were many situations where I felt very odd, not used to Western life. It didn’t help that Swedish was the only language spoken in public. In Lithuania, everything happened gradually, while those who left were immediately immersed in a different life,” she explained.

In 1991, Lithuania’s fate was still uncertain. Trainees in Sweden feared a new occupation and worried that they might have nowhere to return to. Therefore, VMU lecturers, like other researchers, were provided with diplomatic passports issued by the Ambassador to the Holy See, Kazys Lozoraitis. The professor, who has kept her passport to this day, recalled that the document was intended only for diplomats and their wives, but that did not prevent other women from obtaining it too. “It was fascinating; all of us who were in Stockholm at the time bonded like mountaineers or a sea-going crew, and we still meet occasionally and rejoice that we have these unique passports,” Prof. Petrauskaitė said.

According to the professor, the traineeship in Sweden was significant also because seeing an electronic Swedish language corpus there inspired the creation of a Lithuanian language corpus in Lithuania. Thus, in 1994, the Centre of Computational Linguistics was established at VMU and led by Rūta Petrauskaitė.

Prepared a news review in Russian

The events of January 13th led Linas Bulota, a historian and former VMU Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Humanities, to television. Just minutes after the broadcast from Vilnius was cut off on a Sunday night, news began to be broadcast from Kaunas – from the Kaunas studio of the Lithuanian Radio and Television located near VMU.

“All the equipment was switched on the evening before because, as usual on Sundays, an hour-long programme from Kaunas was scheduled to be aired. When the Vilnius Television was seized, the technicians on duty tried to start it up – it worked – and it went live. The broadcasts were led by Vidas Mačiulis, Raimundas Yla, and Raimondas Šeštakauskas, all of whom did their best to disseminate information,” Linas Bulota explained.

As the re-established VMU already had its first visiting professors from abroad, information was also needed in English. That was how Liucija Baškauskaitė, the then Vice-Rector of VMU, came to join the television broadcasts.

“The next day, I came to lectures, and Liucija Baškauskaitė was looking for me. She grabbed me by the arm and said: ‘Linas, I was told you speak Russian well, we need you on television’,” Bulota recalls. This was the beginning of the vice-dean, historian, and lecturer’s acquaintance with television, an acquaintance that would last for years to come.

“I got into television for the first time in my life, having never even spoken on the radio, let alone interpreted. But being a historian, I knew what I needed to talk about. That helped me navigate through all those events and convey them to an audience that might have had doubts,” Linas Bulota recounted.

There was no division

According to Bulota, anxiety, tension, and uncertainty lingered for around a week. Later, “Panorama” was also broadcast from Kaunas, featuring a news summary in Russian, which was later taken over by a Russian editorial team from Vilnius. Linas Bulota and Raimundas Yla began producing the “Krašto apžvalga” (National Overview) programmes and hosted the live broadcast of the Sunday programme “Kalendorius” (Calendar).

Although the entrances to the television studio from the courtyard and S. Daukanto Street were blocked by trucks, and VMU students stood guard at the doors, Linas Bulota has no doubt that it would have been possible to take over the studio in just ninety seconds. The historian recalls that later that same year, during the August coup, the Kaunas television studio was briefly occupied, though only for a few hours.

“Since the order was carried out by local military personnel from Panemunė, they allowed us to take away all the equipment and archives. We hid everything at VMU. That very same day, together with Raimundas Yla, we recorded an episode of ‘Krašto apžvalga’ by the Freedom Monument, ready to broadcast from Juragiai if necessary. However, since the coup in Moscow was suppressed within a day, the soldiers neatly departed, and the people bid them farewell by giving each one a flower. It was done in a nice, cultured manner, without any hostility,” Bulota recounted.

According to the historian, the January events were marked by a special spirit of unity; there was no division: “That mindset of the people… to this day it remains so vivid, it feels as though it all happened yesterday.”