Interdisciplinarity is becoming increasingly necessary today

Assoc. Prof. Evelina Gužauskytė.

The links between fashion magazines and literature, women’s education in the USA and Latin America, domesticity and mythology in eighteenth-century Mexican (then New Spain) paintings, and the myth of Arachne in the work of Gabriel García Márquez are just some of the topics that Evelina Gužauskytė, a PhD in Spanish (Colonial Latin American Literature), teacher of Latin American literature and culture, translator, and Associate Professor at Wellesley College in Boston, will discuss at Vytautas Magnus University (VMU) from May 7 to 14.

As part of the Vytautas Kavolis Interdisciplinary Professorship programme, the visiting scholar will deliver public lectures at VMU and participate in Kaunas Literature Week, where she will moderate a conversation with the Argentine writer Mariana Enríquez.

Information about the lectures.

Assoc. Prof. Gužauskytė, who emigrated to the USA in 1992, has maintained her ties with Lithuania. She not only returns here during summers but also participates in various events and engages in Lithuanian scientific processes. In 2018, she served on an international humanities expert panel tasked with conducting a comprehensive overview of humanities research in Lithuania as part of the national research reform. She also participated in the First World Lithuanian Writers Congress and was interviewed on the topic of dual citizenship.

Gužauskytė (centre) with colleagues at the Wellesley College graduation ceremony.

“Many people ask me how I still speak Lithuanian so well after thirty years in the USA. I have never felt disconnected from the Lithuanian language; it has always been alive in me. It is important to me, my family, my children. I am happy that my daughters, who were born in the USA, also understand Lithuanian very well and speak the language, even if with an accent. Through language, we gain a sense of place, its culture, history, and pulse of life,” says Gužauskytė.

We conversed with the scholar in Lithuanian about the culture of eighteenth-century Mexico, the portrayal of women in texts about the conquest and colonisation of the Americas, feminism, interdisciplinarity, and children’s books.

Your breadth of topics as a scholar appears exceedingly wide-ranging: from literature to fine art, from the history of mapping to clothing. How would you personally describe your field of research?

Broadly speaking, it encompasses texts and visual culture produced during the so-called colonial period, usually delineated as spanning from 1492 to 1810. This period commenced with Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Caribbean islands and extended until the onset of independence struggles in what we now recognise as Latin America, marked by the cry for freedom uttered by Mexican priest Miguel Hidalgo on 16 September 1810, which has been known ever since as “The Independence Cry.”

In my earlier book, I delved into the consonance between the Taíno (one of the predominant indigenous cultures in the Caribbean islands) and Spanish languages, evident in the Spanish and hybrid place names documented by Christopher Columbus in his journal. The book, titled “Christopher Columbus’s Naming in the diarios of the Four Voyages (1492-1504): A Discourse of Negotiation”, was published in 2017 by Homo Liber and translated from English by Miglė Anušauskaitė.

Miguel Cabrera. Spanish and Indian, Mestiza. 18 a. Museum of Mexican History, Monterrey, Meksika.

My current projects focus on the last century of the colonial period. I am interested in issues such as hybridity, the search for identity, and the construction of a national image – more specifically, the self-representation of eighteenth-century Mexico through vestimentary culture and the perception and depiction of its meanings in visual works and texts, including literature.

Why is the topic of feminism important to you?

During the colonial period, in the regions we now refer to as Latin America, the authors of texts and written sources were almost exclusively men: many texts with legal, historical, and literary functions were penned by conquerors, hired soldiers, the so-called scribes (escribanos), as well as by priests and monks who arrived in the Americas to spread the Christian faith. However, the voices, experiences, and perspectives of women are absent in these accounts of events.

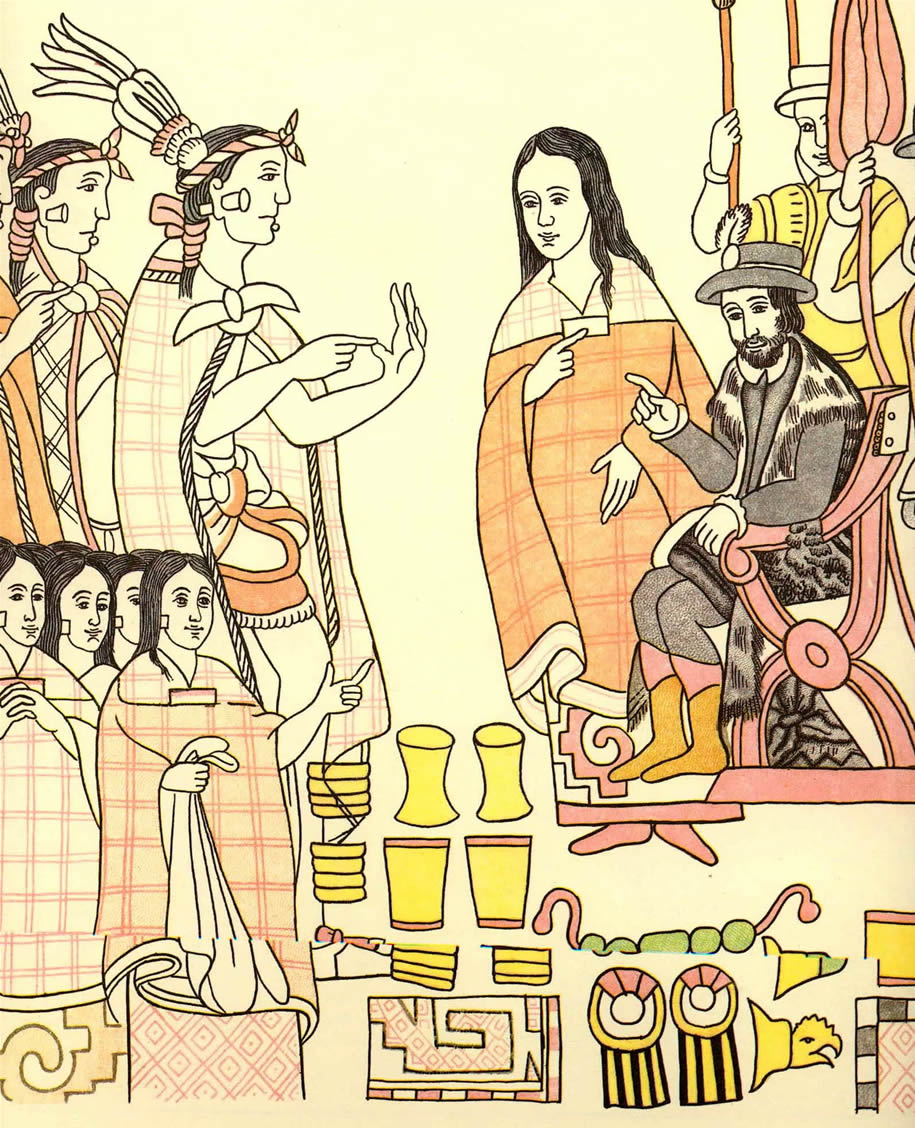

We know, for example, that La Malinche, or Malintzin, a woman of Nahua descent who served as Hernán Cortés’s translator and was also the mother of his first son, played a significant role in the narrative of his conquest of Mexico. Although she frequently appears in pictorial historical documents, she is scarcely mentioned in written texts. Cortés himself only briefly mentions her in a letter to the King spanning hundreds of pages, while Bernal Díaz’s in “The True History of the Conquest of New Spain” (Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España) devotes as much as two pages to her, which is considerably more than Cortés’ text, but surprisingly scant given her role in the dramatic events of the conquest of Mexico, specifically the Triple Alliance (Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan), also known as the Aztec Empire.

Malintzin (La Malinche), Hernan Cortes, and Nahua nobles. Codex Tlaxcala (ca. 1550)

Although there are isolated instances where women contributed as writers, these serve as exceptions that prove the rule. In my current research, I am trying to reconstruct at least a fraction of women’s experiences, their narratives, and their societal contributions by examining the portrayal of women in texts and visual works.

In one of your lectures, you will discuss fashion magazines and their relationship with literature. How can fashion, which may initially appear trivial in the grand scope of history, help us understand both societal processes and literature itself?

In Mexico, and more broadly across Latin America, the first publications specifically tailored for female readers were the so-called calendars (calendarios), which featured literary texts alongside the latest fashion sketches and descriptions. Women from middle- and upper-class backgrounds subscribed to these periodicals – sometimes they were published only once a year, and at other times more frequently – providing them with insights into new sleeve shapes for dresses, the most fashionable skirt lengths, as well as the latest short stories, essays, poems, and excerpts from travel diaries. This way, they would also read novels in serialised form before their full publication. This gave rise to the Spanish phrase “serialised novel” (novela por entregas), and many famous novels were published in this manner. Mexico City is no exception: similar periodicals, offering the choice of favourite hat styles while featuring the most captivating local and translated literature, delighted and enlightened readers in Paris, London, Philadelphia, and Lima.

Reading girl: fashion illustration. Calendario de las señoritas megicanas para el año 1843. Mexico.

You explore the connections between ancient Mexican and Baltic mythologies. How and why could such distant cultures create similar mythical worlds?

This part of my work is more theoretical. Clothing, jewellery, their practical functions, and symbolic meanings were, and still are, important for all civilisations without exception, despite their differing forms. The creation of clothing is a process which, both in Baltic mythology, as insightfully described by Algirdas Julius Greimas, and in pre-Hispanic Mexican cultures, namely the Mayan and the subsequent Nahua cultures (the latter also known as Aztecs), reflects the notions of humanity, becoming human, and birth. Therefore, I am particularly interested in the symbolic functions of clothing, especially the symbolic functions of clothing as expressions of becoming or becomingness.

Myths reflect the fears, desires, and worldviews of the cultures that created them; hence, they reflect the humanity of their creators. Sometimes, there are overlaps, almost repetitions, in the narratives of very different cultures regarding the past, the creation of the world, and the emergence of the feminine and masculine. This does not suggest that these cultures are somehow related or had contact in the past. Not at all. But perhaps what might be reflected in similar perceptions of the world, the other, and the self is the fact that, fundamentally, these cultures, regardless of their geographical origins, share certain common human qualities.

How is being an interdisciplinary scholar perceived in the world of academia? After all, stereotypically, a scholar is probably seen as someone who delves deeply into research rather than covering a broad spectrum?

I believe that even scholars working in interdisciplinary fields have an “anchorage” in one, maybe two disciplines, but the problems they investigate naturally call for, even demand, perspectives from more than one discipline. In this case, if we were to solely rely on narratives written in Latin script, depicting a significant portion of society – women, indigenous peoples still commonly referred to as ‘Indians’, and the millions of people forcibly transported from Africa to the continents and islands of the Americas – our knowledge would be very limited.

But these societal groups have left a vast and rich legacy, which is reflected not only in visual and material culture – such as food and clothing – but also in customs, music, and various other domains. By examining not only texts that depict the conqueror’s gaze but also other forms of cultural expression, we can gain a deeper understanding of the life and imagination of a multifaceted, hybrid, and evolving society.

How do you reconcile such different disciplines? What advice can you offer to those students who are, perhaps, apprehensive about embracing interdisciplinarity?

Students’ apprehension is entirely understandable: for them, it is primarily important to establish a solid foundation, graduate, and acquire a specialisation that they hope will lead to employment after university. This is a pragmatic and sensible approach. However, one of the primary goals of a liberal arts education is to provide students with knowledge and skills in areas that will give them an advantage in any field. These include critical thinking, the ability to discern between false and accurate information, the capacity to defend one’s own viewpoint, to sift through a multitude of sources for relevant information, to participate in a discussion, and to collaborate effectively within teams. These and similar skills can and should be developed during the course of studies, regardless of a student’s chosen specialisation.

When university structures facilitate not only the acquisition of a specific specialisation but also an interest in multiple disciplines, it undoubtedly provides students with an advantage in the labour market and in future studies or projects, enabling them to approach problems from more than one perspective and to find creative solutions. After all, students do not attend university merely to memorise a multiplication table, but to learn how to identify connections between different things.

In fact, interdisciplinarity is becoming increasingly necessary today: technology and design, economics and climate studies, women’s/gender studies and law, medicine and the visual arts are just a few examples of how different disciplines or fields can come together to offer much-needed and interesting points of intersection. Nonetheless, I think it is crucial to have a strong foundation in at least one specific field before trying to conquer two or three others.

Let’s talk about your other area of activity, which you refer to as “creative writing”. During your visit to the children’s book festival “Live Letters”, you will also introduce your children’s book “The Adventures of Brigita Begemotaitė and Her Friends”. Why did you decide to write a children’s book?

The book “The Adventures of Brigita Begemotaitė and her Friends” was written during late evenings. Throughout the Covid years, I began telling stories to my daughters, who were then in primary school, which gradually evolved into a book. After finishing the text, I started looking for an illustrator and collaborated with the talented artist from Zarasai, Gintarė Laurikėnienė. Then, the editing and layout work took place. I am delighted to present to present the book at Kaunas Literature Week. To differentiate somewhat between my academic work and my venture into the field of children’s literature, I signed the book under the literary alias Jūra Smiltė (approx. transl. Sea Sandgrain).

Jūra Smiltė sounds very nostalgic. What do you enjoy most about Lithuania when you return here for your summer holidays?

Most of all, the sea and the sand on the Baltic coast. And, of course, the cold beetroot soup.