“We Chose to Be”. VMU, the Experience of Freedom, and January 13th in Prof. Agnė Narušytė’s Recollections

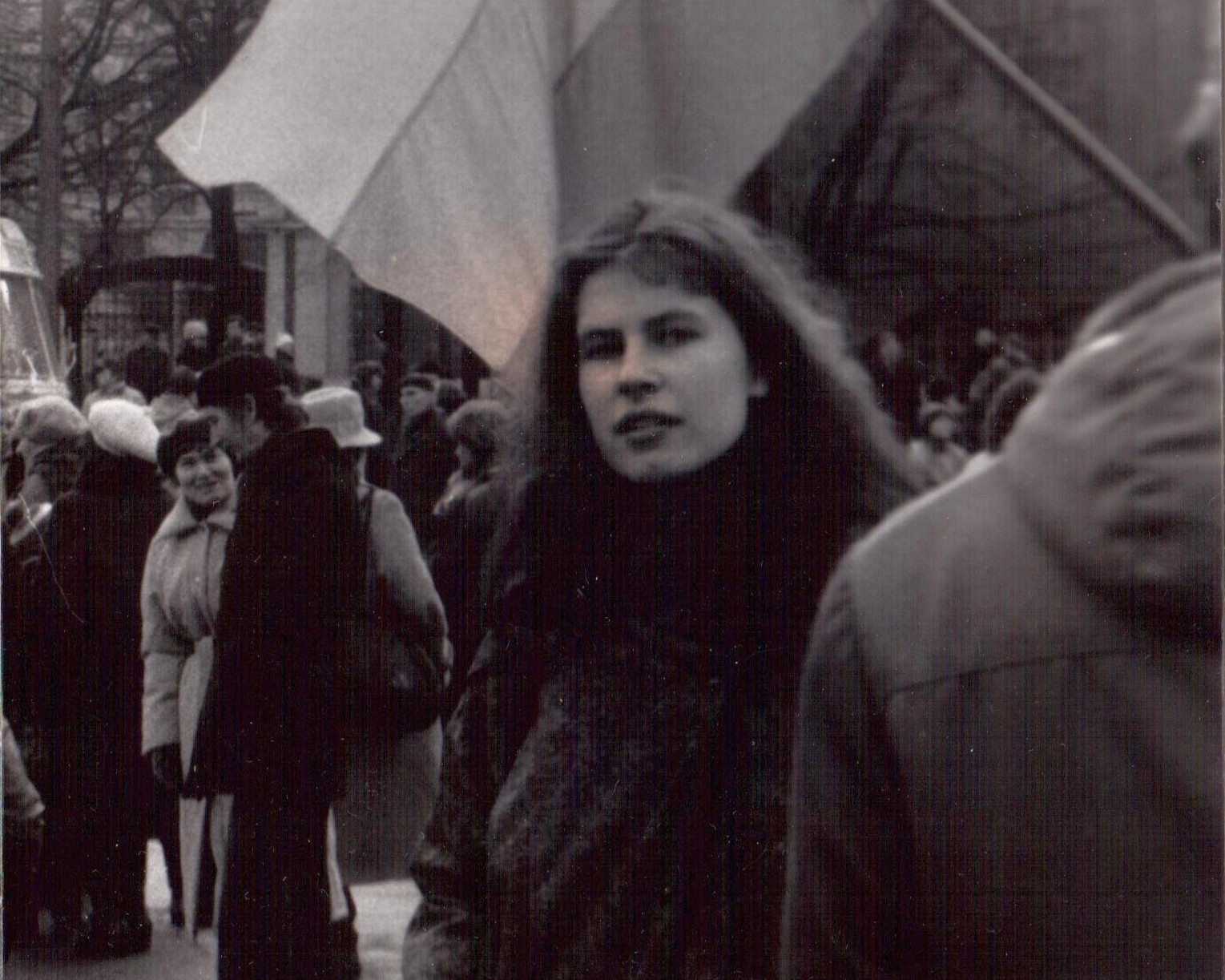

Agnė Narušytė at a Sąjūdis rally in 1989 (photo from a personal archive; photographer unknown)

13 January 1991 in Lithuanian history marks not only a political turning point, but also a time of personal choices. That night, people chose to be – to be at the Seimas, the TV Tower, Lithuanian Radio and Television, and university buildings. It was a choice arising from an inner conviction that freedom requires unity.

On the occasion of the Day of the Defenders of Freedom, art historian Prof. Agnė Narušytė – then a VMU student, defending freedom not only by keeping watch at the Seimas, but also at the university, which was born of the same freedom-inspired idea – shares her memories of the first years of Independence, the newly re-established Vytautas Magnus University (VMU), and the bloody events of January 13th.

A University Born of the Idea of Freedom

When we speak today of VMU as a Western, open, and community-minded institution, it is easy to forget that these values did not arise of their own accord. In 1989, when the university had only just been re-established, they were consciously chosen and shaped – together with the first students. This is precisely how Prof. Narušytė – who at the time enrolled at the university not only for her studies, but also for the promise of living differently – remembers VMU.

“We enrolled at this university precisely because it promised to be Western,” she says. Re-established as a continuation of the University of Lithuania of the interwar period, VMU offered what at the time sounded almost utopian: studies that focus not on narrow specialities, but – following American traditions of higher education – on a broad field of chosen subjects, the opportunity to choose, to make mistakes, and to explore. “All of us in the humanities – future philosophers, historians, philologists, ethnologists, art historians – were together at first. Only later did we begin to specialise.” Prof. Narušytė is delighted that this made it possible to get to know a wide circle of people who later chose different specialities.

First History and Theory of Arts thesis defences at VMU, 1993. Agnė Narušytė is standing on the right in the first photo and is sitting in the centre in the second photo (photo from a personal archive; photographer unknown).

There was also a different kind of relationship at VMU between teachers and students. “When the university was being shaped, there was a real concern for its quality; teachers would invite us and say: we are shaping the university together. Tell us what you want, what you think,” the professor recalls. “And we did tell them, and we felt as if we were truly taking part in the shaping of the university. It was wonderful and like a kind of gift in my life. Although the final decisions, of course, were made by the university authorities, and sometimes they made decisions that we did not agree with. Then we would fight. And sometimes we would win,” says Prof. Narušytė, adding that such open dialogue was rare at that time. The quality of the university was also ensured by carefully selected teachers: “We were taught by specialists who came from the United States and by the very best specialists selected in Lithuania,” the professor says.

The first cohort of art historians at VMU, 1993. Agnė Narušytė is third from the left at the top (photo from a personal archive; photographer unknown).

Internationalism also played a major role at the university re-established in line with Western traditions. Daily lectures in English, teachers from the United States and other foreign countries, and preparation for international exams opened up a world that was still difficult for most of Lithuania to access. “After passing an international English-language exam, we were able to continue our studies abroad. Many of us did so.” The professor recalls the opportunity to delve into the latest academic theories while abroad, and the two suitcases of photocopied scholarly books she brought back from a university in Prague – books that were so scarce in Lithuania at the time. It was VMU that opened this window to the world: “Here you could feel the breath of the free world,” Prof. Narušytė says.

The turbulent first year of independence

However, for a university full of ideas of freedom – and for Lithuania as a whole – 1990 was not a peaceful year. Soon after the restoration of Independence on 11 March, the country had to endure an economic and energy blockade. “There was no petrol, no hot water, no heating,” Prof. Narušytė, who at the time was living in a VMU dormitory on the outskirts of the city, recalls. “My friend and I would walk to lectures; she would teach me English, we would speak English the whole way, make up stories and laugh. We said we were getting some exercise, getting some movement – we made such fun out of all of this that it was good even without that petrol,” the professor recalls.

When rumours spread in the spring that the Soviets might try to take back the buildings that had been handed over to the university, Prof. Narušytė and other VMU students guarded the university premises day and night. “This watch was different from standing around the Press House – you were inside, so you could even doze off. But we didn’t sleep at night; we talked, messed about in the building where there were no teachers. We would go out for a walk as well; when we reached the military compound we would cast stern looks at the soldiers and then return to stand guard,” Prof. Narušytė recalls the watch that lasted three days and nights. She and other VMU students guarded the university building in shifts: “We didn’t divide ourselves formally; those who could went. Those who had kept watch at night would go back in the morning to sleep, and in the evening we would be on watch at the university again. Of course, we missed some lectures, but preserving the university was more important.”

On watch at VMU, spring 1990 (photograph by Agnė Narušytė)

“In the end, the Soviets seemed to relent, and we received word that there was no longer any need to guard the university – its buildings would not be taken back. And yet we spent those three nights on watch in good spirits – we got to know all the students in Kaunas, not only from our own humanities faculty, but also the ‘numbers people’, the students from the Faculty of Economics,” A. Narušytė says, recalling the event that brought the VMU student community together.

The night of January 13th: an orange, a prayer, and the decision to stay

By autumn, the crowds keeping watch could no longer turn the Soviets back so easily, and tension was rising. It reached its climax on 13 January 1991. Prof. Narušytė remembers this night in minute detail. Although she had planned to go on watch at the TV Tower, which was closest to her home at the time, she ultimately found herself at the Seimas: “Although the Soviets tried to deceive people by spreading the word that they would not attack that evening, crowds still gathered to keep watch. I was planning to go to the TV Tower, but then a friend called – she had arrived by bus from Alytus and invited me to keep watch with her at the Seimas. I agreed. Now we sometimes talk about how she probably saved my life – after all, I was prepared to lie down in front of the tanks if necessary. We were prepared to stand and not let them through; we understood how important television was,” the professor recalls.

Having finally arrived at the Seimas building, at first together with her friend and later with her younger cousin, Prof. Narušytė kept watch all night. “We walked around, drank tea. I clearly remember the brown slush of snow that had been carried in by so many people onto the floor of the nearby café’s toilet. And the stunned crowd when the first shots were heard and the news spread about tanks heading towards the TV Tower,” the professor shares her memories of the night of January 13th. Then, as Prof. Narušytė recounts, there was silence, followed by Vytautas Landsbergis’s voice. Warning of the danger, he urged people to go home. “We all shouted ‘No!’. And although I felt that fear of death, this ‘No!’ was like an oath that nailed my body to the ground and didn’t allow me to run. There were some who ran. But there were only a few of them, and I don’t blame them, but we all stayed,” the professor says.

Barricades and bonfires after the night of January 13th (photo by Agnė Narušytė)

What also remained in Prof. Narušytė’s memory was the realisation that she might not live to see the morning: “We were standing in a small group when some stranger gave me an orange. My cousin and I shared it. I remember eating it and thinking that this was the last orange I would ever eat in my life. I will not eat anything else, because I am going to die.” Soon afterwards, tanks began to move towards the Seimas. “People drew closer together and began to pray. I was not a believer, but at that moment I had nothing else, only prayer. We prayed aloud and the tanks passed by,” Prof. Narušytė says, adding that this still did not make her believe in God. “I did not come to believe in God, but in people’s will – when something is truly important to people, they can achieve it.”

“Later I read various documents and accounts and learned that there had been many calls, both from Lithuania and from the United States, urging that the tanks pass. But at that moment it really felt as if the shared prayer of the people had helped,” Prof. Narušytė notes. At dawn, barricades began to be built near the Seimas, and the television and radio broadcasts that came on air confirmed that Lithuania was still standing.

A positive memory and connection

Although January 13th was full of pain, and the funerals of those killed that night were heavy and oppressive, this day is still associated with something positive for Prof. Agnė Narušytė. “That good feeling comes from the fact that there were very many people and they all chose to be,” she says. “I felt the fear of death, that night I was terribly afraid, but there was such a firm belief that Lithuania must be free, that the Independence restored on 11 March was more important than life itself. I suspect that many of those who had gathered felt the same.”

Agnė Narušytė (photo by J. Stacevičius)

The professor also recalls receiving a call from a coursemate in Kaunas in the first days after January 13th. “I picked up the phone and it was a coursemate, a historian. We weren’t very close friends or anything, but he asked how I was doing, and we talked. When he said that everyone in Kaunas – at VMU, all our coursemates, all our friends – was alive and well, I was filled with such a warm feeling,” Prof. Narušytė says, describing the connection she maintained with Kaunas and the university.

This experience, the professor says, became fundamental – a basis for believing that people, when united, can resist anything. And even today, as we commemorate January 13th, it reminds us not only of the mourning for those who died defending freedom, but also of what Lithuanians were able to achieve by standing together.